We are now in a position to find the most basic equations to do calculations on satellite orbits in the plane.

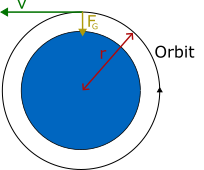

First, let us imagine a satellite which is in a circular orbit around Earth, as seen in figure 1. There is only one force acting on the satellite, which is the gravitational force of the Earth. The force is given as

where is the mass of the Earth,

is the mass of the satellite and

is the gravitational constant. We know that the centripetal force

equals the force of gravity

:

Simplifying and solving for the velocity gives

where is called the gravitational parameter. For Earth it becomes

. Here,

is the Earth mean radius and

is the altitude of the satellite above Earth’s (mean) surface. Then, the velocity above is that which a satellite must have to maintain a circular velocity around Earth at a given radius or altitude.

We know that distance equals mean velocity times the time spent moving that distance, or . Using the circumference of a circular orbit

and orbital time period

, we have

Solving for time, we get

For a general ellipse this expression is very similar:

where is the semi-major axis.

As long as the satellite is not firing its motors, its mechanical energy will always be conserved (in a Keplerian orbit; relativistic effects could cause non-conservation). The mechanical energy is given by

Note that the potential energy is a constant for a general gravitational field, given only by the semi-major axis for the orbit. This is valid for all ellipses. Usually we rewrite the equation to

Enter the ideal rocket equation . The assumption for the equation is that the satellite burns its engine for a short time, which is usually true for a satellite with a chemical rocket engine. When planning a satellite orbit, it is important to have a so-called ‘delta-v budget’, which states exactly how much fuel is needed for the satellite to reach a given orbit and to stay there. As several

can be added together, the total mass needed for the total

can be easily calculated. We will come back to this shortly.

<< Previous page – Content – Next page >>

This article is part of a pre-course program used by Andøya Space Education in Fly a Rocket! and similar programs.