Liquid rocket motor

To burn a rocket motor, three things are needed: fuel, oxygen and heat. Burning fuel and oxygen is always an exothermic reaction which provide its own heat to continue burning. Heat is needed to kick-start the reaction.

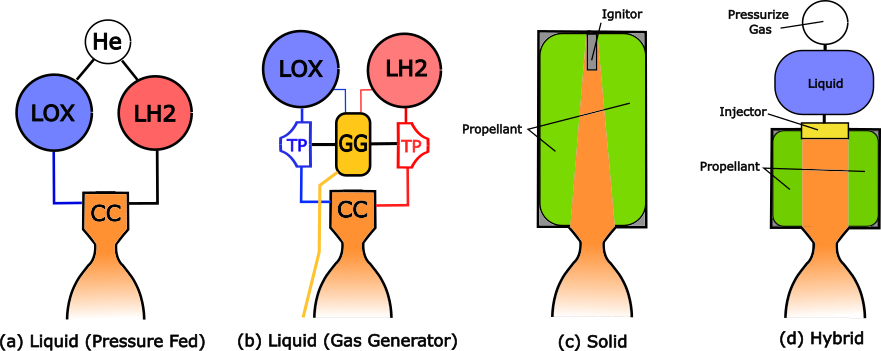

Liquid motors have both the fuel and the oxidizer in liquid form when stored in the rocket tanks. The tank pressure is usually relatively low. Different types of liquid motors exist, which differ in the way the fuel and oxidizer are forced into the combustion chamber. A simplified sketch of two types is seen in figure 1(a) and 1(b). For small, simple liquid rocket stages, the fuel and oxidizer can be forced into the combustion chamber by using an inert gas, usually helium (which does not contribute to the combustion) as seen in figure 1(a). In this approach, ‘only’ tanks, plumbing and some electronically controlled valves are needed in addition to the combustion chamber and nozzle. The extra gas and gas tank structure increases the overall weight of the rocket stage (this might be a favorable trade-off however, given how simple the solution is). Moreover, the weight, volume and pressure inside the helium tanks increases with increasing size of the rocket, and for rockets above a certain size this solution is not practical.

Larger liquid motors will always have a turbopump (TP), as indicated in figure 1(b), to pump fuel and oxidizer into the combustion chamber. This will typically lead to complex practical solutions. The pump is driven by burning small amounts of fuel and oxidizer burned inside a so called gas generator (GG). This is usually done with a large oxygen to fuel or fuel to oxygen ratio to keep the temperature relatively low inside the pump) to drive a «water wheel» that spin a turbofan at extremely high speeds, increasing the pressure of the fuel and oxygen.

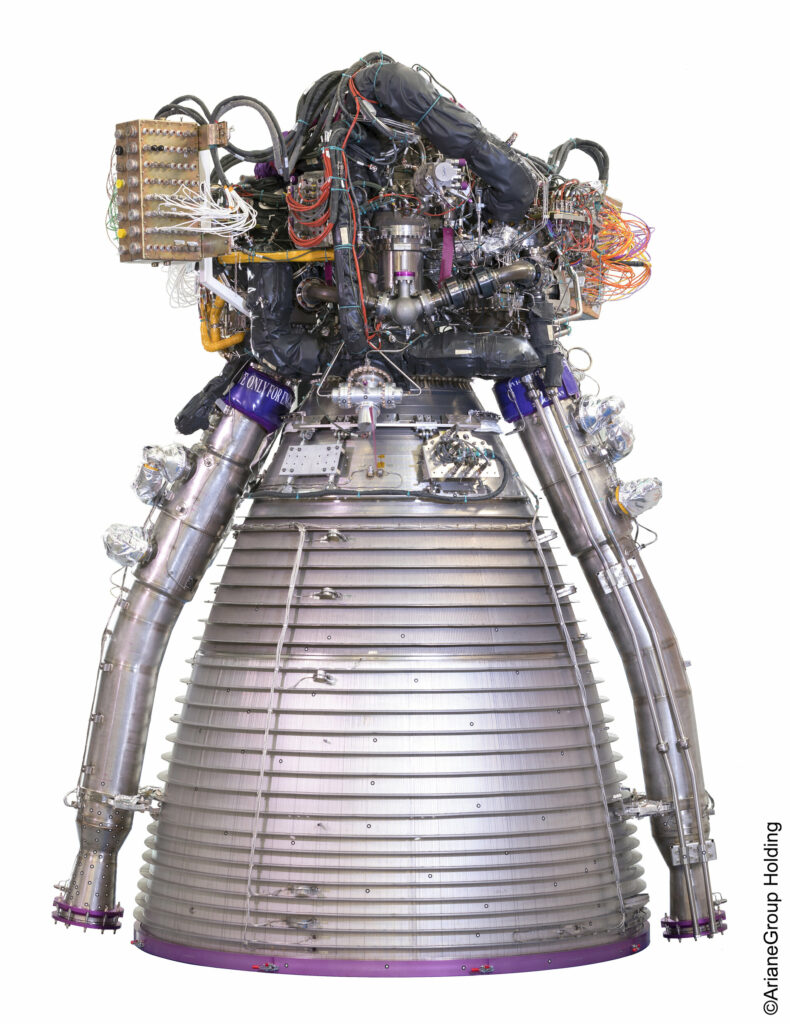

For the most efficient motors, the fuel and oxygen used by the gas generator in the turbopump is forced into the combustion chamber again in order to utilize any remaining energy (keep in mind that the gas generator is inefficient, due to the large oxygen to fuel or fuel to oxygen ratios to keep the temperature low). This is called a staged combustion motor. The open cycle motor, on the other hand, discard the gas coming out of the turbopump. The open cycle is less efficient (lower Isp), but is generally simpler to build. An example of an open cycle motor is the first stage core liquid motor of Ariane 5, the Vulcain 2, seen in figure 2. The exhaust pipe seen on the side of the nozzle, which is attached to the turbopump partly visible embedded within the piping, is used to vent out the turbopump gas.

The nozzle can become very hot, and some motors, usually large in size, need to cool the nozzle down. This is done by letting some of the cold fuel pass around in tubes outside of the nozzle. When this is done, the fuel is working as a cooling agent. The nozzle can become very hot, and some motors, usually large in size, need to cool the nozzle down. This is done by letting some of the cold fuel pass around in tubes outside of the nozzle. When this is done, the fuel is working as a cooling agent. The fuel is forced into the combustion chamber after passing through the nozzle piping.

Solid rocket motors

The other type of rocket motor most often used is the solid motor, where both the fuel and oxidizer are in solid state. The fuel and oxidizer is blended together and molded into a shape within a metal structure called the casing. This casing is the mechanically bearing structure. Inside the propellant blend, there must be a volume where the fuel and oxidizer, which is released in gas form when heated up, are mixed and combusted before reaching the nozzle. See figure 1(c) for the parts making up a solid motor.

The propellant is usually ammonium perchlorate (oxidizer) and extremely fine aluminum powder (fuel) mixed with Hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene (HTPB is a translucent liquid with a color similar to wax paper and a viscosity similar to corn syrup) as a binder, in addition to some catalysts. The result is a black rubbery structure. Using a variation of catalysts and different mixture ratios of oxidizer, fuel and binder, the designers can vary the characteristics of the motor. The shape of the propellant will determine what the thrust curve looks like, that is, how the thrust varies with time after ignition.

The advantage of a solid motor is that it can provide huge amounts of thrust, and therefore it is often used as a booster, making a satellite launching rocket gain high initial velocity before using higher-efficient liquid motors to gain horizontal velocity above the densest part of the atmosphere. Another advantage is that it is very simple, and when it is ignited it burns until it runs out of propellant (or until a catastrophic failure occurs). This is also one of the disadvantages of such a motor: it can never be switched off by command and can not be throttled as a liquid (and hybrid, explained in the next section) motor can. It is usually less efficient than liquid motors, with a typical specific impulse being below 3000 m/s in vacuum and 2800 m/s at sea-level.

Hybrid rocket motors

The third rocket category is hybrid motors, where one of the propellants is in solid form and the other in liquid form. Classic designs have solid fuel and a liquid oxidizer, but some reversed designs—i.e. with liquid fuel and solid oxidizer—also exist, though the latter is more challenging to make practical. Historically, hybrid motors have not been very popular, but advances in the technology are making hybrid motors increasingly popular. The most famous rockets using hybrid technology are SpaceShipOne and SpaceShipTwo, owned by Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic.

Figure 1(d) shows an example of a hybrid motor using hydrogen peroxide as the oxidizer and a rubbery fuel. A catalyst is used to help with the decomposition of the oxidizer as it is forced into the combustion chamber (where the fuel is). Note the use of nitrogen to force the oxidizer to the combustion chamber. The fuel is usually metallic. The specific impulse can be upwards to 4 000 m/s. Hybrid motors are usually quite simple in construction, but still more complex than solid motors. They have a higher specific impulse than solid state motors, but are throttleable and can be shut down as liquid motors can. The biggest problem of hybrid motors have been problems increasing the hybrid motors low burn rate as the mixing between the oxidizer and fuel is more difficult, but this is improving. They are considered as very safe since the fuel and oxidizer can be stored and shipped individually, and each component by itself is completely safe (though they might be toxic).

Electrical Thruster

One fourth motor type that is worth mentioning is electrical thrusters. Electrical motors have extremely low thrust (on the order of a few to hundreds of milli-Newtons) but very high specific impulse. This makes them unusable as rocket motors, because of the inability to counter the gravitational force. However, on satellites they are very practical and the motor can achieve over 40 000 m/s of specific impulse as of 2018. The low force means that the motor needs to run for long periods of time, but cuts down the overall amount of fuel needed to reach a given delta-v. One example is the ABS-3A, a communication satellite in geostationary orbit which is the first commercial satellite to only use electrical thrusters. The satellite had less than half of the lift-off mass than a satellite based on a chemical motor (about 1 900 kg, compared to the about 4 000–5 000 kg on satellites using chemical rockets), with the main mass difference being due to the small amounts of fuel needed, only about 100 kg of fuel needed for orbital insertion and station keeping.

See more about the chemistry behind rocket fuels, with focus on the very toxic hypergolic fuels (used on some rockets and many satellites, with the Russian Proton rocket being the most well-known rocket):

<< Previous page – Content – Next chapter >>

This article is part of a pre-course program used by Andøya Space Education in Fly a Rocket! and similar programs.